Director Alexander Payne, whom I learned to appreciate through two earlier films, About Schmidt (2002) and Sideways (2004) wrote for his 2017 comedy drama Downsizing with long term partner Jim Taylor a script which could not have been more foresightful. Dr. Jørgen Asbjørnsen, a Norwegian researcher and inventor of a medical procedure known as downsizing, which turns a full-grown man into a 12 cm lilliput version of himself, summarizes in a scene which lasts barely a minute all worries about an anthropogenic 6th mass extinction:

Homo sapiens will soon vanish from the Earth … No matter how the end will come, environmental disaster, pandemic disease, unbreathable air, impotable water, not enough food, nuclear winter, some combination of them all. Relatively soon the earth will purge itself from of human life and God knows of how many other species … not a really successful species, this homo sapiens, barely 200.000 years. Alligators have survived 200 million years with a brain the size of a walnut.

Only five years after the film’s release, we are still in the grip of a pandemic disease and at the brink of a global food crisis caused by an unnecessary war between two of the world’s largest wheat exporting nations. Clean tech investments are surging worldwide and a tech savvy elite led by the world’s richest man, Elon Musk, is in a gold rush for saving the planet or a small part of the human species with technologies beyond the reach of people like you and me. In light of these events, I felt compelled to watch Downsizing once more for I recalled what made this movie in my humble opinion so brilliant was its indirect message: technology will not save mankind; it can at best support its salvation if charged with the right values. True salvation, however, must come from a new kind of social contract.

The film’s rating and reviews indicate that this message did not reach the average audience. Downsizing is a subtle piece of art which cuts across many genres – I would even say it creates or consolidates a new genre. Some critics describe it as science fiction, others as comedy drama, again others as both. Film critic Chris Knipp writes in exemplary manner:

What seemed to start out as a sci-fi satire winds up as a fable about doing good, and about whether it is possible to save the human race. Payne meanders. He’s all over the map. His film, which began with a sci-fi conceit with strong satirical possibilities, winds up being aimless and maudlin.

I couldn’t disagree more. Payne created a film which will soon be named in one breath with the Truman Show, Her, 1984, Bicentennial Man and Metropolis, Fritz Lang’s 1927 masterpiece with which it has so much in common, the scifi, the two worlds apart and the class struggle. The film’s complexity and brilliance come from its deep plot which touches upon many crucial questions and modernity’s defining challenges.

It starts out with a criticism of the capitalist consumer economy which puts a huge pressure upon average families. Paul Safranek is middle aged but still pays back his student loan. His wife works in a mall, suffers from chronic neck pain and dreams of a large mansion, while the couple still lives in the run-down house in which Paul was born. Cash stripped as they are, the promise of multiplying one’s wealth (and doing something for the environment) comes like a gospel of salvation, when they meet their miniaturized friends at a high school reunion.

This first part of Downsizing turns the data of post-growth economists like Andrew McAfee into a cinematic narrative: There are two personas in our modern economies which he calls Bill and Ted. Bill, the mid aged average guy without university education and Ted, the mid aged average guy with university education. Since the 1980 their livelihoods have been breaking apart, leaving Bill substantially more vulnerable to the dramas of life: unemployment, financial problems, disease, and eventually divorce and social isolation.

If you are aware of how Western societies have – despite constant economic growth over the last 50 years – lost in general wellbeing and how little the rest of the world was able to improve living conditions, then you notice already during the first 15 minutes that this film is not about the a futuristic solution to climate change but about declining social inclusion; it is a radical and immensely elegant criticism of modern capitalism, which makes some (technologists) excessively rich at the expense of a new global caste of exploitable human resources. Downsizing is a fable about deteriorating social capital in developed economies as described by Francis Fukyama in The Great Disruption.

The gloominess of reality for most average members of modern societies is abruptly enlightened with a message of hope when Paul Safranek’s high school friend shares personal details about why he miniaturized himself and how the experience is so far. However, what seems to be a miracle solution to the Safranek’s problems with being underdogs in the capitalist pecking order, soon turns out as yet another criticism of our modern way of life, where we seem to satisfy every craving with consumption.

Instead of showing a true alternative to our exploitative and materialistic lifestyle, Downsizing brags with more of the same, only with less environmental impact and for much less money. Don’t forget that everything you buy in smurf world is around 3000 times smaller and thus much cheaper. Inspired by their friends’ decision, the Safraneks visit Leisureland, one of the luxury lilliput communities in New Mexico. There they meet Neil Patrick Harris (whom my generation remembers well as Doggie Howser M.D.) as real estate broker showing off what an indebted white couple can afford in Reality 2.0.

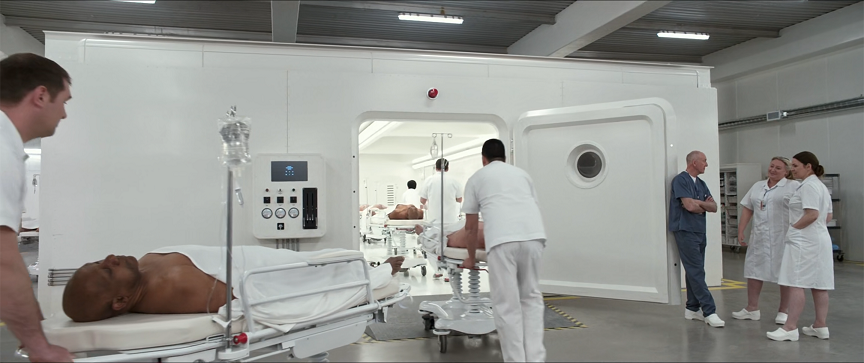

The disturbing downsizing procedure which reminds at least my generation of the final solutions which the Nazi machinery found as an answer to the Jewish question. Scalable technological solutions which alter the nature of human life and / or violate basic human rights and dignity do yield a nightmarish dimension. Payne shows this horror of the past in a sci-fi version, but the pictures of gas-chamber like rooms where people are downsized and the medical preparation for the procedure (including the removal of tooth prosthesis) can be unmistakably connected and are a dramatic warning to not let such darkness enter our world again.

That all the money in the world cannot buy genuine relationships, personal warmth and a person one can rely on in times of need, is what Paul Safranek learns when waking up from the downsizing procedure. He moves into his miniature palace but without his queen who decided in the very last moment that she is not ready to abandon her grown-up life. After an unequal divorce, Paul loses the mansion, moves into a small apartment and has to pick up a low-end job to sustain himself. This second transformation when already small and in Leisureland is itself a pointed parable about how modern consumer society distracts us from finding an exit from the maze of materialism and a path towards well-being.

It makes me recall Buddhist Matthieu Ricard who teaches that we don’t need to consume in order to compensate our boredom, lack of purpose or frustration:

“Although we want to avoid suffering, it seems we are running somewhat towards it. And that can also come from some kind of confusions. One of the most common ones is happiness and pleasure. But if you look at the characteristics of those two, pleasure is contingent upon time, upon its object, upon the place. It is something that — changes of nature. Beautiful chocolate cake: first serving is delicious, second one not so much, then we feel disgust. That’s the nature of things. We get tired.”

Happiness is within us as an eternal seed. What we need to find is not a new world (neither in Leisureland nor on Mars), but the habits which let us tap into that happiness and let it grow into a healthily rooted tree instead of a feeble seedling which requires daily fertilizing. Paul Safranak finds this seed in himself when meeting Ngoc Lan Tran, a political fugitive who was forcefully downsized because she organized social and environmental protests in her home country Vietnam. She now makes a living in Leisureland by cleaning the apartments of wealthy dwarfs, like the one of Paul’s neighbor Dusan, a Yugoslavian fixer who traffics rare produce like Finnish vodka or Cuban cigars from the giant world to insatiable lilliput lips – another brilliant strike at modern consumer society and the promise of technology mending the black hole of material cravings no matter what size our brains are.

It is through Ngoc Lan Tran that Paul is introduced to Leisureland’s underworld, an enclave of servants and migrant laborers who dwell outside its protective concrete walls. Paul’s first bus ride with Ngoc Lan Tran to “Little Mexico” is in my opinion the defining scene of this film – that’s why you see it as the first still in this article. It takes him (a second time) out of his white middle class bubble and reveals the slums of disenfranchised dwarfs. When the bus emerges on the other side of Leisureland’s gated community, Paul encounters slum like conditions which are nothing like what he had expected. Despite material scarcity it is there that he finds meaning.

This is when Downsizing’s narrative strikes a third time against the prevailing economic system established by pax americana. The tunnel is another cinematic parable for the fence which separates the US and Mexico but also the EU from the African continent. It is a metaphor for class struggle, lack of social inclusion, and connects Downsizing directly to the narrative of Metropolis where the working class does not live outside but under the world of the wealthy. It is latest at this point that the audience should reach a Eureka moment. Top notch science, high end technology, perfect procedure, but still the outcome is the same as in reality 1.0: class struggle, social segregation and lack of equality in opportunities. There seems to be something wrong with the technology or with the people in power using it: authoritarian decision makers of capitalist or communist provenience.

While the container high rises in Downsizing remind of the Uyghur concentration camps in China’s Xinjiang province (as leaked this week) which the government euphemistically calls vocational schools, the marginalization shown is much more like what we know from Western capitalism, which creates abundance for a few and scarcity for many. Strangely it is here that Paul Safranek grows his seed of happiness when he supports untiring Ngoc Lan Tran in caring for those who nobody else cares for. Paul resigns from his purpose deprived job in Leisureland and applies his premed qualification to service the inhabitants of Little Mexico.

Psychologists have long tried to put such individual transformation into words. The best I have found so far was put forward by neurologist Viktor E. Frankl who survived the WWII Nazi concentration camps.

“For success, like happiness, cannot be pursued; it must ensue, and it only does so as the unintended side-effect of one’s personal dedication to a cause greater than oneself or as the by-product of one’s surrender to a person other than oneself. Happiness must happen, and the same holds for success: you have to let it happen by not caring about it”.

Paul does both. He first surrenders to the cause of helping those who are in need and then surrenders to Ngoc Lan Tran instead of giving his life meaning by following the Downsizing founding community around messianic Dr. Jørgen Asbjørnsen into a fallout shelter which shall protect them from arctic methane melting. Even this thread of the script felt enlightened because the founding community which tried salvation for humanity at large is now shown as a cult which separates itself from the rest of the world after dramatically watching a last sunset.

The film set out to provide a sci-fi solution to climate change and offered to the middle class of industrialized economies, which lost most significantly in the process of globalization, the gospel of limitless consumption with very little waste created thereby, but it ends by revealing a universal truth: that technologies which are conceived as a solution to environmental problems only, will continue or even aggravate our social challenges. Downsizing echoes thereby what Pope Francis wrote in his Encyclica Laudato Si:

The human environment and the natural environment deteriorate together; we cannot adequately combat environmental degradation unless we attend to causes related to human and social degradation.

The climate crisis is without doubt the defining crisis of our era. However, there is another crisis looming behind it all and this crisis of about consciousness. While high tech and green tech investments surge, our societies continue to fall apart. Wealth accumulation in the hands of a few has reached according to economist Thomas Piketty pre-WWI levels, social welfare systems corrode, and automation puts more and more people out of their jobs. A solution to the climate crisis must be a design for all (DfA) not just for a few who can afford to buy electric cars or passive houses or downsize themselves voluntarily.

Paul Safranek’s transformation from proud mansion owner to humble Samaritan is therefore another important message hidden in this film which appears as a light at the end of the tunnel: we won’t find happiness and well-being in more consumption and thus continuous economic growth. We might however find it in a world (behind the concrete walls of capitalism) where we give ourselves away to others, where we practice altruism and create a different form of growth, one which takes place both in a material (phenomenal) and a spiritual (noumenal) dimension.

It takes meaning for the individuum to experience this new form of personal growth and economic incentives to lead a meaningful life would make the transition towards well-being so much easier. Our economies are however stuck in a system which creates scarcity and drives pleasure seeking nihilism. And we do it against better knowledge. Behavioral economist Daniel Kahneman showed in cooperation with Gallup already in 2009 that happiness does not increase (in the US) beyond an income of USD 60.000. It does however decrease significantly the less you have below this threshold.

The script for the development of a sane human society is therefore very clear: we need to strive for a conditional annual UBI of – PPP appreciated – USD 60.000, which is connected to a meaningful occupation. Paying people around the world for providing social and environmental ecosystem services which are logged in a system of distributed value accounting is therefore worthy of a concerted effort, if we want to listen to experts of happiness and meaning research like Daniel Kahneman.

In the end its not about whether we downsize ourselves in a material dimension as long as we have the bare minimum to meet our needs. The light at the end of the tunnel is the reduction of our wants – no matter how big we are – and listening more to the needs of others. Its about growth created through sharing or like Viktor Frankl said:

“What man actually needs is not a tensionless state [of wealth and boredom] but rather the striving and struggling for some goal worthy of him. What he needs is not the discharge of tension at any cost, but the call of a potential meaning waiting to be fulfilled by him.”

Further reading:

- https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/movies/movie-reviews/downsizing-review-1032268/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Downsizing_(film)

- https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2022/may/22/food-crisis-is-what-happens-when-global-chains-collapse-we-might-need-to-get-used-to-it

- https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/services/sustainability/assets/pwc-the-state-of-climate-tech-2020.pdf

- https://taylorholmes.com/2018/01/17/problems-movie-downsizing-explained/

- https://www.chrisknipp.com/writing/viewtopic.php?f=1&t=3791

- https://www.mingong.org/blog/film-review-metropolis-1927-and-its-current-relevance

- https://www.ted.com/talks/andrew_mcafee_what_will_future_jobs_look_like/transcript

- https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/57986.The_Great_Disruption

- https://www.ted.com/talks/matthieu_ricard_the_habits_of_happiness

- https://www.pursuit-of-happiness.org/history-of-happiness/viktor-frankl/

- http://www.darkmatteressay.org/pope-francis-by-wim-wenders.html

- http://www.vatican.va/content/dam/francesco/pdf/encyclicals/documents/papa-francesco_20150524_enciclica-laudato-si_en.pdf

- http://www.mingong.org/blog/book-review-rise-of-robots-technology-and-the-threat-of-a-jobless-future

- https://www.ted.com/talks/daniel_kahneman_the_riddle_of_experience_vs_memory/transcript

- https://www.gallup.com/analytics/247355/gallup-world-happiness-report.aspx

Una respuesta a «Downsizing our Upscaling?»

[…] and Francis Fukuyama as the end of history. On this subject, it is always recommended to watch Downsizing and ponder on its relevance in connecting the social and environmental […]