These last few weeks were marked by a few events of global importance. We discussed in the last blog entry the requirement of a social contract 2.0 and why nationalist and profit driven global sporting events are obsolete. Today we will take a look into COP27 and COP15, indigenous stewardship, and how capitalism has shaped our relationship with the planet.

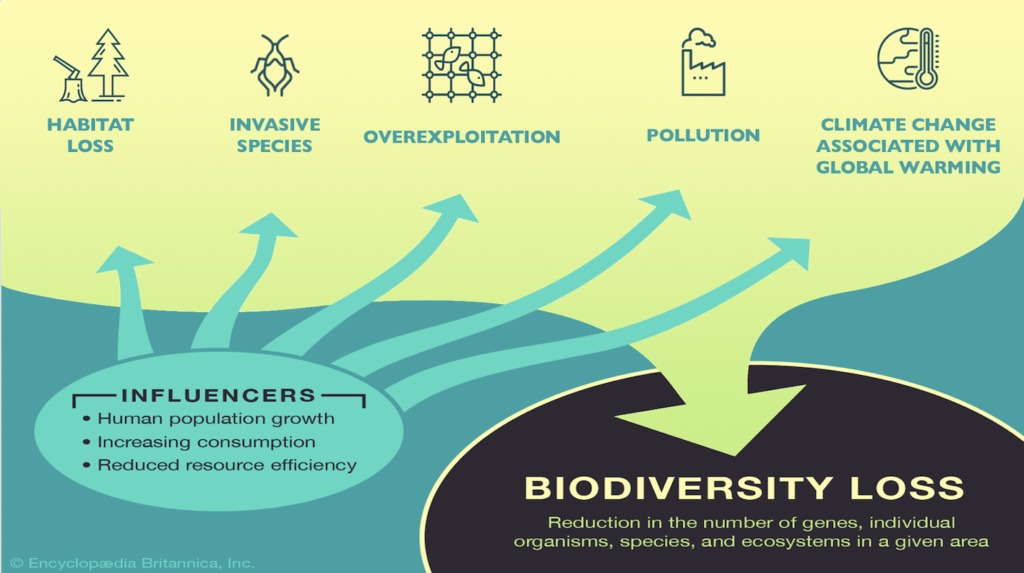

Some of us are aware that two global environmental conferences take place every year. This year it is COP27 on climate change and COP15 on biodiversity loss. COP27 – which was titled by the Guardian as HOT AIR SUMMIT – disillusioned last month in Egypt once more about the possibility to derive top down solutions from an assembly of diplomats and experts who decided to meet in Sharm El Sheik, a Red Sea holiday destination. The host country Egypt has sentenced in December 2021 the dissident Alaa Abd El-Fattah to five years of jail for spreading fake news. Is this the place to hold talks on the future of the planet?

Putting politics aside, COP meetings have become substantial corporate agendas. Like FIFA world cups and Olympic Games, they appear as another global franchise, where the fortunate (of politics not sports) meet and greet. I have even found articles about the last Olympic Games and COP27 which read as if written about the same type of event: numbers of delegates representing countries as an indicator for undefined performance. Complaints by NGO delegates about unaffordable and inflated accommodation pricing are a repeating story. Government officials rarely complain: their bills are settled by taxpayers.

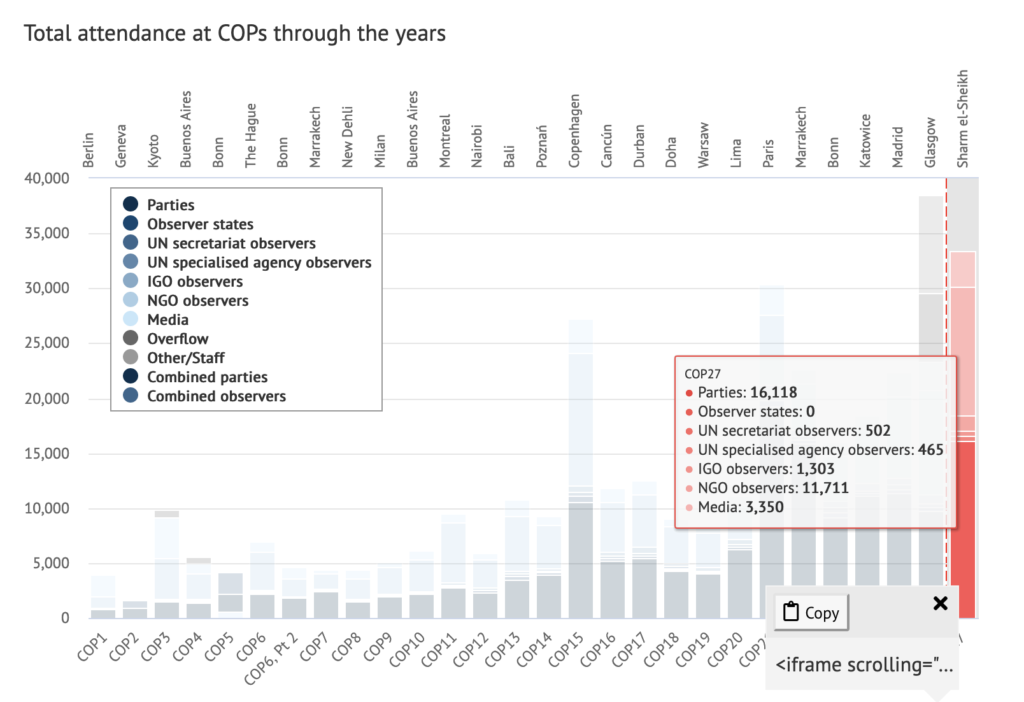

COP gatherings are for some the pinnacle event of annual conference tourism, and like last year in Glasgow not only the number of delegates, but the choice of travel utility provides evidence that humanity has handed over its fate to the wrong people: dozens of private jets were counted at the airports of Cairo and Sharm El Sheik, forming the tip of an iceberg in carbon footprint caused by almost 40.000 delegates attending a conference, which literally produced hot air. How many delegates does a productive conference on climate change or biodiversity loss need? Where should it take place? What should be negotiated that can be actually enforced?

If Covid-19 has taught us one thing, then that home office and remote work is possible. It does not only allow more time with our families; it saves money and helps us to create a low carbon footprint by avoiding unnecessary traffic. Why then do government officials and NGO delegates have to meet in person and how many participants are meaningful if they have to meet? The sciences of organizational psychology explained that the most productive meetings have fewer than eight attendees. Even if very diligent COP27 delegates attended 4 meetings a day, they would not have been able to meet more than 400 people in the course of the 12-day conference in a productive manner.

Without going more into the numbers of proofing the futility of large-scale conferences, we need to address the psychology which motivates their ballooning existence. My radar perceives FOMO (fear of missing out), a lack of self-awareness in regard to one’s carbon footprint and some motivational drives which are located in Maslow’s pyramid on level 4 (esteem) instead of level 7 or 8 (self-actualization or transcendence). It’s difficult to check participants on their motivation, but don’t we need a majority of negotiators who are qualified both in the subject as well as through their personality? In order to make such gatherings meaningful, the attendees need to be motivated by transcendence and self-actualization, otherwise no relevant outcome is to be expected.

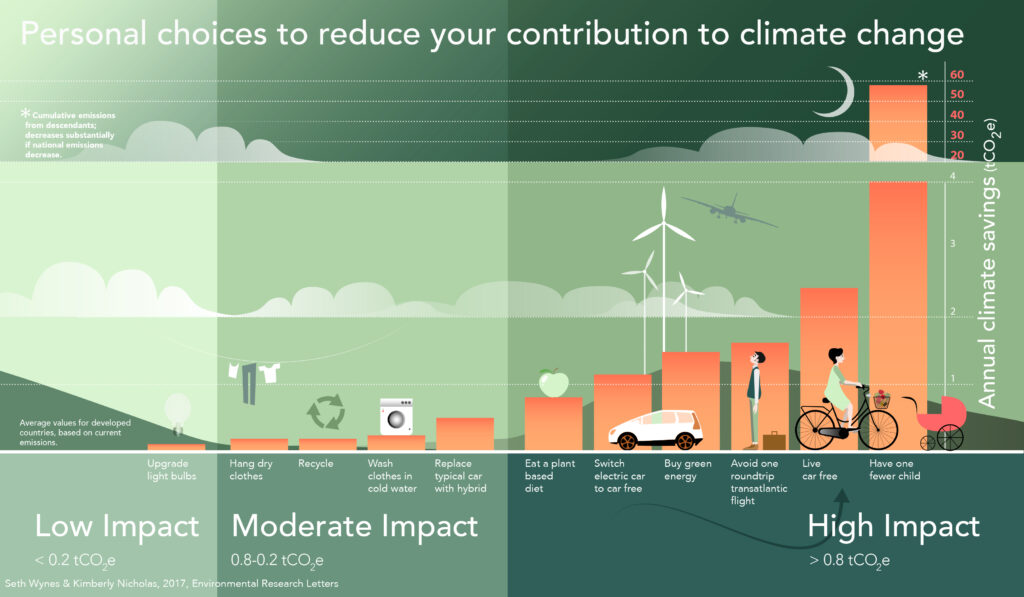

A few words on our personal carbon footprints: I don’t like to live in a world, where I have to calculate every action I take in regard to its environmental impact. It makes life too difficult to live. But: we need to be aware that we have limited natural resources available, which we have to share among more and more inhabitants of a single global ecosystem. Without fairness and responsibility things simply won’t work for the next generations. Therefore, a basic understanding how I create my carbon footprint and which lifestyle choices help to reduce it, is required. This understanding might well become the very foundation of future compulsory education.

While aviation accounts only between 2.5-3.5% of the global greenhouse gas emissions, it is an important contributor to one’s personal footprint, which averages at around 5 tones of CO2 per capita globally as this in a nutshell video explains. Travelling by plane is like butter on bread or cream on coffee: it is more on top of an already substantial collective and per capita carbon footprint. An economy flight from London to Cairo generates 1.2 tons of CO2, a business class flight 2.3 tons, and a first class flight 3.5 tons, making first class travelling on commercial planes as climate damaging as travelling on private jets.

We are told that we have to reduce our individual carbon footprint to 2 tons a year by 2050 to avoid a 2˚C rise in global temperatures, but every participant to a COP conference did create at least 1.2 tons of CO2 on travelling alone. In my experience, government officials rarely suit themselves with economy class tickets. They often fly first class and enjoy such perks to make up for their lower annual wages compared to corporate executive management. Probably more important than how they travel is the frequency: many participants to COP conferences are frequent flyers.

What kind of traveling procedures does public administration require to reduce overall greenhouse gas emissions? Carbon footprints are directly connected with wealth: the more money available, the bigger your carbon footprint. Looking at the people who attend Olympic Games, FIFA World Cups, Tennis Grand Slam tournaments and international conferences, it’s clear who needs to cut back first. Self-imposed standards would certainly be better than laws, but both is necessary, unless we find an out of the box solution which makes mass event tourism obsolete.

Indigenous Stewardship vs International Diplomacy

Running up to COP15 in Montreal (Dec 7-19), I watched a few talks about indigenous stewardship and the mutual love relationship between native people and their land, jointly organized by TED and Nia Tero, a nonprofit strengthening guardians of territories and cultures. Valerie Courtois, a member of the Canadian Innu community explained why international conservationists and diplomats ought to learn from indigenous practices: “If we take care of the land, the land takes care of us.”

It was in particular her talk, which made me ponder on the concept of being indigenous. There are only about 400-600 million people on the planet which are qualified as indigenous, but we can assume that still fewer practice indigenous lifestyles. While I believe in the values of Nia Tero, i.e. following the indigenous leadership and wisdoms to secure the health of our planet, I feel that the label “indigenous” is contrary to maybe 50 years ago, again fashionable, and the emphasis on being indigenous creates yet another in-group, which leaves 7.5 billion people in a new out-group.

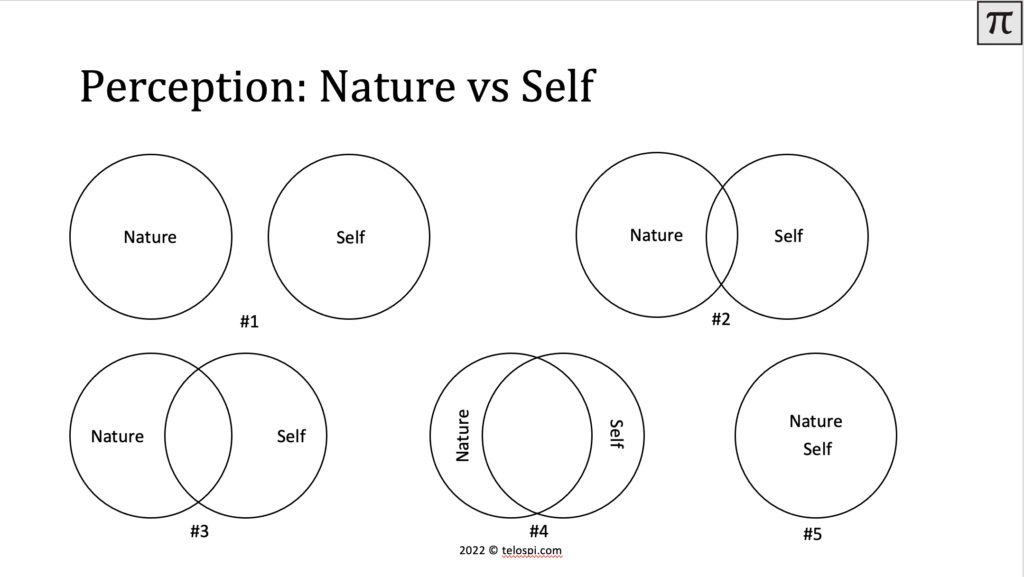

Stewardship of the planet can be practiced by every human being, if we are granted access to land. Considering the alarming state of the environment, we need to make sure that humanity at large embraces the concept of being indigenous. The overview effect is experienced by astronauts when they view our planet from outer orbit. It induces a cognitive shift from being a nation state citizen to becoming a child of Mother Earth. Indigenous stewardship induces a similar cognitive shift of being separated from to being connected with the land. A gradual transformation in self-perception is the result; and this must be the supreme goal of all 21st century education.

What does it take to qualify as indigenous? How could a curriculum of stewardship look like? How do we turn ourselves and our children into guardians without being a direct descendant of chief Big Bear? While we need to learn from indigenous practices on how to become a guardian, we must be aware that with climate change more and more people will be pushed off their land and therefore must connect to new territories within a short time. If it takes several dozens of generations to qualify as indigenous, then we will run out of time to spread these practices with required impact.

What comes to my mind as a potential source for such a curriculum is a book written by psychologist Jean Liedloff who spent several years on and off with indigenous tribes in Venezuela. She described in “The Continuum Concept” the bond between the newborn and his mother by being physically much closer and for a much longer time as this is the case in most “modern civilizations”. In the same way that it is paramount to be close to one’s mother in order to develop emotional skills, it is important to be close to the planet in order to develop environmental empathy. Observing how nature detached our lives have become overall, it is no surprise that even the most enlightened international contracts negotiated by diplomats and experts, won’t work. The transformation has to happen bottom up as a movement for general well-being.

If the target is more nature connection, then we need to look into how such a transformation can be achieved. One thing is already pretty obvious to me: it will entail a land reform and the land reform must entail a tax reform along the lines of Geoism. Nature connection can’t happen if more and more people spend their lifetime in Caves of Steel as Isaac Asimov wrote in 1953 about the cities of a dystopian future. People need to be on the land and with the land in order to love the land. Depriving more and more people of access to land, will result in even more nature alienation.

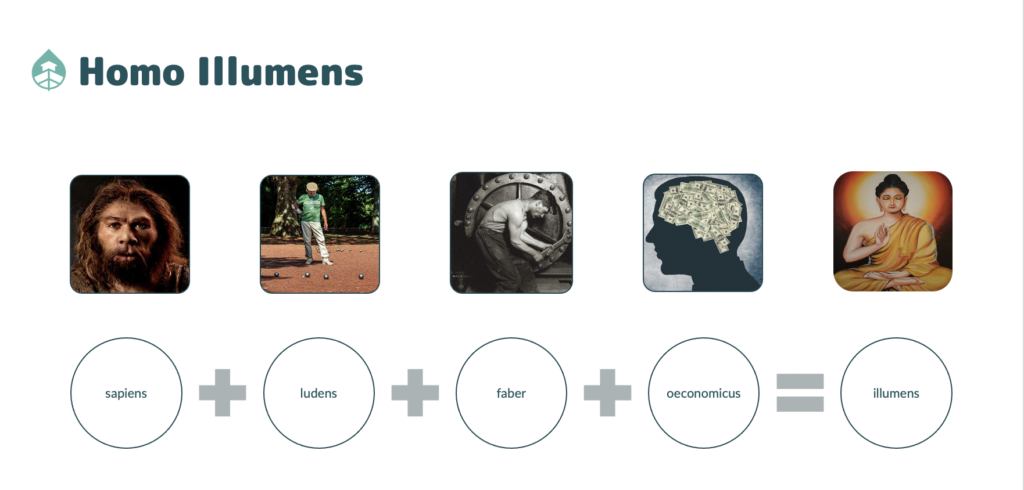

The planet is a superorganism and we are part thereof. By reserving 30% or more to biodiversity conservation as it is being discussed at the moment in Montreal, we break up the holistic entity of this superorganism and fail to start with conservation in the ecosystems in which we live. 90% of Japanese, 80% of Americans, 75% of Europeans, 60% of Chinese and 40% of Indians live in cities; and 2/3 of global greenhouse gases are generated in cities. Biodiversity loss can’t be avoided by sealing off large parts of the planet, but by changing our culture and our values; thus, the change must happen in our education systems. If not there, where? As long as our schools produce homo economicus as the standard product, we are on the wrong track.

What we need is a complete overhaul of the industrial education system. We need education which does not aim at the production of university professors, but one which mines deep for the various talents and competencies which are buried in every single human being. We need to celebrate diversity and trust in the contribution, each one of us can make to the human family. We can make this transformation and despite the fear which automation instills into labor markets, a future of robots and algorithms will make it possible to spend more time on the pursuit of interests and passions – if we share wealth fairly.

One premise for a sustainable lifestyle is however access to land. The half farmer half X movement which was started in Japan by Naoki Shiomi lays out a practical vision for nature connection and sustainable food production: spending 50% of one’s time working the land to live off the land, grows an intrinsic – indigenous like – connection with the land. The practice establishes the love relationship which Valerie Courtois described in her TED talk; if we eat the food from the land which we till, twe make sure that the soil in which it grows is healthy. We are self-responsible about the use of pesticides, fertilizers and farming techniques. Being a farmer brings a human being into direct contact with the land and absurdly enough is the most direct path to democratic decision making. Only when we understand the connection between the health of the land and the ecosystems in which we live, we are knowledgeable enough to decide over means of production rather than matters of consumption.

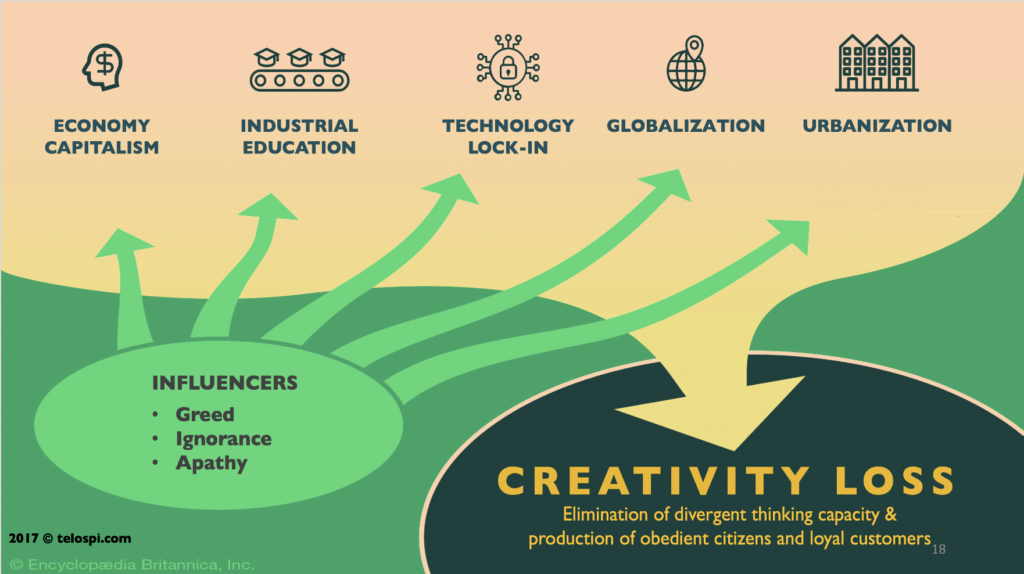

Training children early on through repeated nature exploration about the connection between the environment and the self, develops systems awareness and ecological intelligence. I am convinced that such training also teaches that greed, apathy and ignorance are not the values which create a joyful co-existence. Instead of meeting for COP27 and COP15, we should discuss how we redistribute land and how we restructure our education systems to produce more guardians. We should discuss how our schools manufacture a homo sapiens or even better a homo illumens. It is time to not only think but take measures to produce a new human being which is capable of sharing and caring.

This project has launched last summer a new functionality which empowers everybody to become a guardian of your hometown. No need to wait for international laws or government approval. No more helplessness. Let’s start with the transformation of the planet and ourselves. Now. Get a rope or a measuring tape and explore your neighborhood. Take pictures of the trees you encounter, record their GPS coordinates and map them on the ARK. Trees, as implausible this may sound, are a safe path on your journey to global citizenship. Trees are semi-permanent natural objects which create in our brains the landscapes that become ecosystems. Trees do not only grow roots but help us to grow roots in our understanding of the planet as a gigantic interconnected organism.

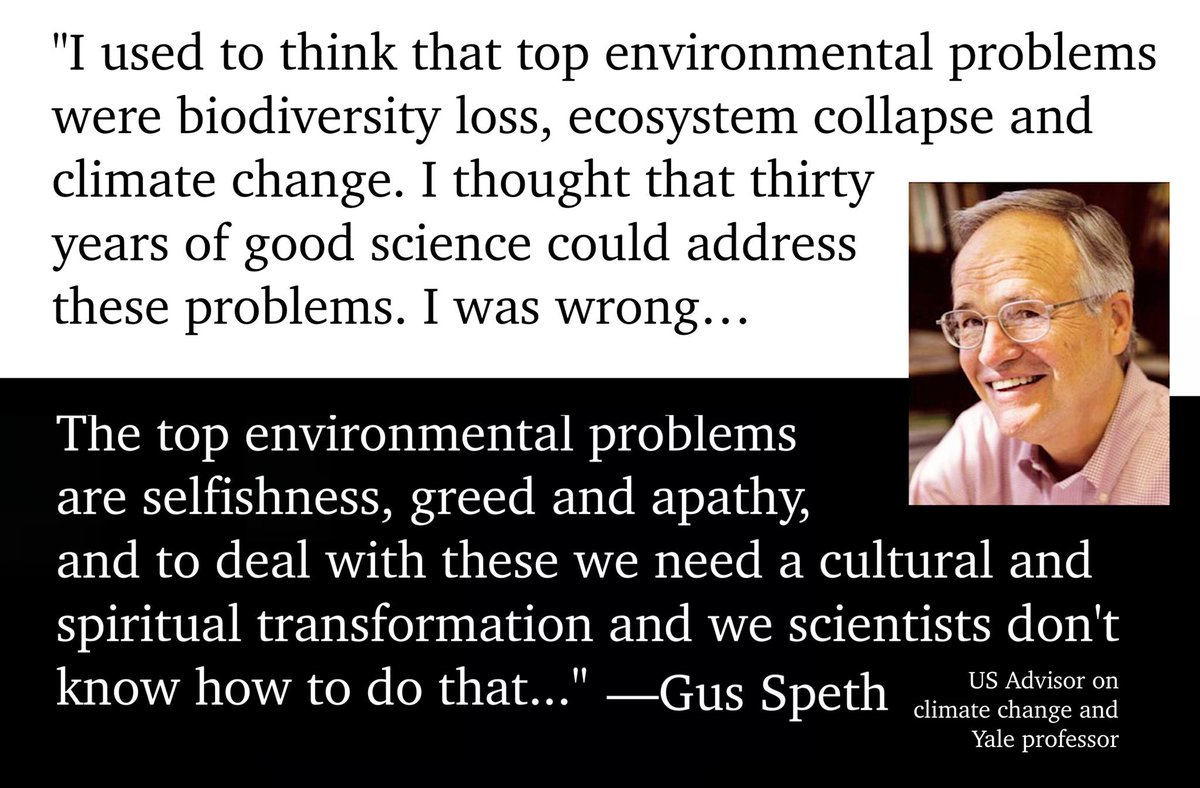

Scientists and politicians meet to discuss climate change and biodiversity loss since 27 and 15 years respectively, yet we know in the words of environmental lawyer Gus Speth, that they are only effects and not causes. The drivers of the environmental destruction we witness and inherit to our children are greed, apathy and ignorance. What does it take to convert these drivers into generosity, caring and mindfulness? Scientists don’t have an answer to this question because there is no methodology for a cultural transformation, one which could be applied in a laboratory setting or tried with small group of volunteers. We can instead listen to Derek Sivers, think about what it takes to start a movement and how these insights relate to the prisoner’s dilemma.

Indigenous stewardship should be seen as part of an integral education model, which has the outdoors as learning setting and familiarity with the natural world as a decisive learning objective. The overall learning aim, however, should be the ability to maintain individual well-being and contribute thereby to collective well-being. If one has acquired these two abilities, I would call this person mature and issue graduation papers. It is interesting to observe that these abilities are not so much connected to age. There are 12-year-olds who do already have caring calm, generous hearts and focused minds; giving them purposeful work to do makes them early on valued members of society, that is guardians who take care of our common home.

Further reading:

- Damian Carrington in The Guardian, The 1.5C climate goal died at COP27 – but hope must not

- Valerie Courtois on TED, How Indigenious Guardians Protect the Planet and Humanity

- The Guardian, What are the key outcomes of COP27 climate summit?

- BBC, How many private jets were at COP27?

- Paul Axtell in Harvard Business Review, The Most Productive Meetings Have Fewer Than 8 People

- Robert McSweeney in Carbonbrief, Which countries have sent the most delegates to COP27?

- Center for Science Education, What’s Your Carbon Footprint

- Kim Nicholas, High-Impact Actions for Individuals to Reduce Greenhouse Gas Emissions

- Global Footprint Network, Footprint Calculator

- The Nature Conservancy, Carbon Footprint Calculator

- My Climate, Flight Calculator

- The World in Data & In a Nutshell, Who is Responsible for Climate Change?

- Visual Capitalist, Carbon Emissions Per-Capita By Country

- Jean Liedloff, The Continuum Concept – in search of happiness lost

- Isaac Asimov, The Caves of Steel

- Sarah DeWeerdt, Your carbon footprint may have more to do with your wealth than your location

- Madeleine Cuff, COP15: What is the 30 by 30 biodiversity target and is it enough?

- Heige Egner, Non-Territorial Nature Conservation? On Protected Areas in the Anthropocene

- Naoki Shiomi, In the beginning, Half Farmer Half X was a concept for saving myself

- Derek Sievers, How to start a movement

- Knut K. Wimberger, On the Education Crisis and the Prisoner’s Dilemma