In 1833, the English economist William Forster Lloyd described the theoretical over-use of a common resource. Cattle herders sharing a common parcel of land on which they were each entitled to let their cows graze, as was the custom in English villages, put more than their allotted number of cattle on the commons. For each additional animal, a herder could receive additional benefits, while the whole group shared the resulting damage to the commons. If all herders made this individually rational economic decision, the common could be depleted or even destroyed, to the detriment of all.

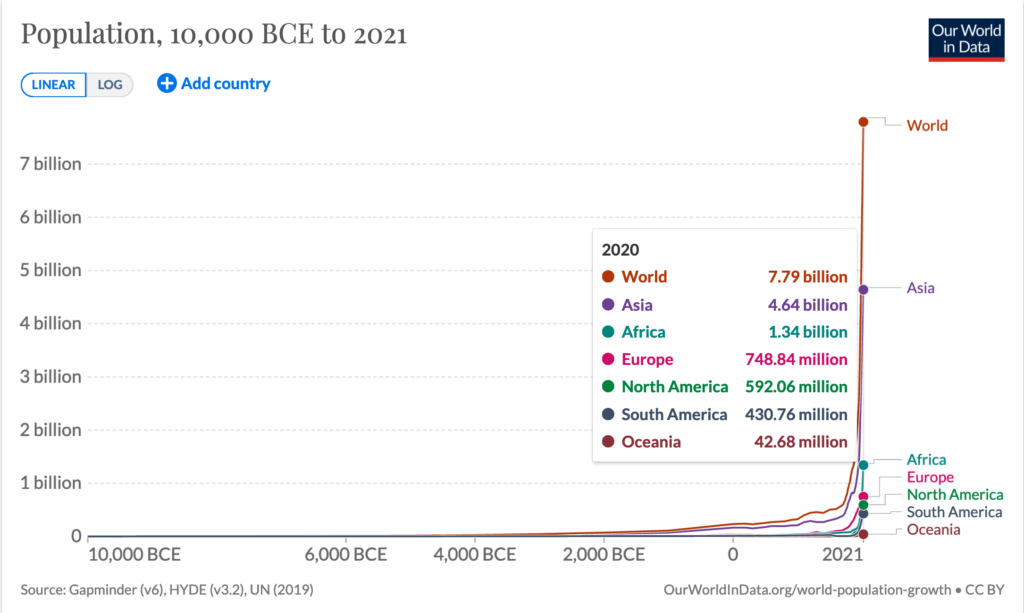

The population of the United Kingdom was 13.57 million and the world population about 1 billion respectively in 1833. It had just started the long and steep growth curve which is meanwhile known from many charts showing the industrial revolution and its impact on our species. The human population was 49.79 million in the United Kingdom and close to 4 billion globally in 1968, when ecologist Garrett Hardin explored in his article “The Tragedy of the Commons”, published in the journal Science (1). The essay derived its title from the pamphlet by Lloyd, which he cites, on the over-grazing of common land:

Therein is the tragedy. Each man is locked into a system that compels him to increase his herd without limit – in a world that is limited. Ruin is the destination toward which all men rush, each pursuing his own best interest in a society that believes in the freedom of the commons.

— Garrett Hardin, The Tragedy of the Commons

We write the year 2022 and the world population has doubled since Garrett Hardin’s 1968 article. Yet, so much of what he wrote half a century ago remains true, in particular the half-hearted measures liberal politics create in Western nations as an answer to the depletion of commons. Western economies face a serious challenge since democracy and freedom are deeply intertwined concepts which have received through capitalist godfathers like Adam Smith a religious underpinning. Freedom without responsibility has become an intimate part of democratic capitalism and capitalist democracies.

The Enforcment of Morality Is System-Sensitive

Hardin can and should be criticized for his opinions on immigration and “unqualified reproductive rights” but before we focus on his shadows, lets highlight the lucid observations which this professor of human ecology made at the intersection of biology, technology, politics and law. The most important might be that morality is system sensitive and that the laws of our society follow the pattern of ancient ethics, and therefore are poorly suited to governing a complex, crowded, changeable world.

Hardin echoes with this statement what Isaac Asimov and Al Bartlett have expressed on a different occasion: human dignity (and democracy) ends when a crowd queues up for a single toilet (2). But he takes this thought example deeper into the legal realm and notes that the Western strategy of augmenting statutory law with administrative law produces a government of men which asks single bureau administrators to evaluate the morality of acts in the total system and makes them prone to error and corruption.

In effect, Hardin claims that we have installed an industrial governance mechanism with which we manage the finite resources of a post-industrial and over-populated world; and he notes as human ecologist bluntly that “space” is no escape, because the per capita share of the world’s goods must steadily decrease with an increase of population. In this sense his “down to Earth” analysis was already 1968 substantially ahead of contemporary outer space entrepreneurs who consider Moon or Mars as alternative habitats for our species.

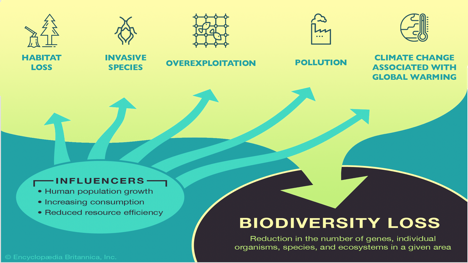

Hardin believes that commons are only justifiable under the conditions of low-population density, but as the human population increases, the commons has to be abandoned in one aspect after the other. First, we abandoned the commons in food gathering, enclosing farmland and restricting pastures and hunting and fishing areas. Somewhat later, we saw that the commons as a place for solid and liquid waste disposal would also have to be abandoned. Recent plastic pollution and over-fishing has started a discussion to shut down the oceans. We still struggle to close our atmosphere as the largest commons of all to air and radiation pollution, but CO2 certificate trade shows that it might soon disappear, too.

Freedom (to exploit infinitely), Hardin argues rightly, is not anymore, a desirable moral objective (but has it ever been?); and he elaborates that Adam Smith’s concept of the “invisible hand” has created a dominant tendency of thought in the Western democratic and capitalistic world that decisions reached individually, will in fact, be the best decisions for an entire society. He explains that the tragedy of the commons is actually a tragedy of freedom and quotes the philosopher Alfred Whitehead: The essence of dramatic tragedy is the solemnity of the remorseless working of things […] the futility of escape can be made evident in the drama.

Commons Need Moral Management

It is my intention to show that Hardin’s opinion, while eloquently put to paper, is of flawed logic and more than that, flawed morality. Hardin builds with his essay on the tragedy of commons a strong case against capitalism, yet he fails to observe that the freedom to exploit as the very essence of capitalism was at any given time a morally undesirable objective – and instead of weakening capitalism, he strengthens private property as one of the key pillars of capitalism. By only looking at the consequences of limitless exploitation by adding up the number of conscienceless actors, one will not be able to derive a moral code which can be sustained in a world of limited resources that need to be shared amongst a growing population with at least theoretically same rights. Hardin avoids the subject but writes essentially about class struggle. The problem he describes is how much the capitalist class agrees to share with the working class in order to allow for a life in dignity.

Instead of arguing for a change of the economic system to e.g. an enlightened form of communism, in which freedom is not anymore understood as freedom to exploit but the obligation to share (and thereby being able to enjoy other freedoms), he concludes that finite resources ought to be distributed amongst a small population and calls for “abandoning the commons in breeding.” In effect, Hardin, does not ask for a change in morality but justifies the prevalent moral code on which the United States were built: take (from the natives), exploit land and people (within certain limitations) and exclude others as you please (from enjoying its benefits).

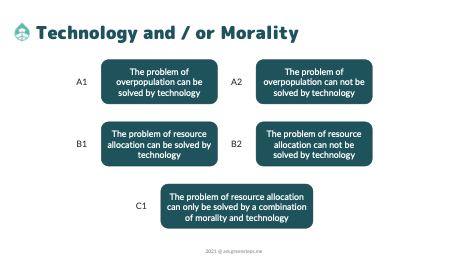

Hardin argues for a change on moral grounds but reveals himself as a belligerent opponent of change. This observation is important as he opens his essay with a statement that applies to himself: It is fair to say that most people who anguish over the population problem are trying to find a way to avoid the evils of overpopulation without relinquishing any of the privileges they now enjoy. He implicitly divides this group of people in two subgroups, one which thinks that the population problem can be solved technologically and the other (to which he claims to belongs) which thinks that the population problem can be solved with a new moral codex of giving the right to breed only to a selected few.

This line of argument, as smartly put forward as it is, is foul. Hardin creates two camps and tells the reader that he is part of the second. He however reveals himself in this essay as being a member of the first group which does not want any change in morality but a technology like a medical procedure which removes reproductive functionalities to control population. Knowing that his 1968 essay was written only a few years after the invention of the contraceptive pill, it reads like a pamphlet for global application of this precise weapon which is the product of advanced biochemical science and technology (3).

The problem in Hardin’s essay starts in my opinion with the assumption that only population size and not also resource distribution needs to be addressed. We certainly agree with the fact that the over-exploitation of commons leads to undesired consequences of climate change, biodiversity loss and eventually the demise of humankind. But I disagree with how Hardin pretends that birth control is a moral solution to the distribution of resources. Birth control has in the case of China between 1978 and 2021prevented an estimated 400 million human lives (4); and while the rest of the world needs to be grateful for this sacrifice the Chinese people have made, the policy has also shown how the enforcement of birth control in a totalitarian state creates suffering, privileges and unfairness.

We have confirmed above that the contraceptive pill (as well as medical procedures with the same effect) is a technological solution to population growth without limits; and we shall see that technology does always entail questions of morality. The discussion should start with morality and from there guide the development and application of technology. The discourse will immediately touch upon the philosophical and psychological subjects of having and being, of self-centeredness and compassion. Mark Twain is credited with the proverb “Law controls the lesser man; right conduct controls the greater one.” The same proverb is known in Chinese as 礼不下庶人,刑不上大夫 and most likely dates back much further since it is considered a part of Confucian doctrine. The reality however shows us that it is the economic system which determines the behavior of the lesser and the greater man alike.

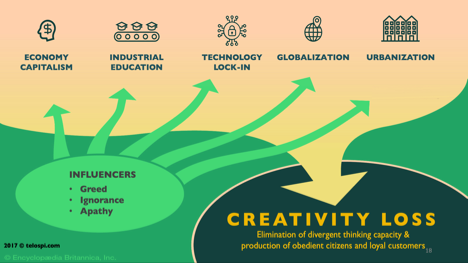

Asystem which is based on selfishness, greed, apathy and ignorance as environmental lawyer Gus Speth once remarked, causes biodiversity loss, ecosystem collapse and climate change (5). He seems to agree with Garrett Hardin that science and technology does not have solutions on these problems and concludes similar to Hardin that a spiritual and cultural transformation is required. Yet, the two differ in their opinions like day and night. Speth calls for a true change in moral standards towards compassion, generosity and stewardship, while Hardin wants to preserve the planet by keeping greed, apathy and ignorance of the ruling class towards the people unchanged. Speth argues for being, Hardin for having.

A spiritual and cultural transformation must start in the realm of economics, rewarding a desired behavior with some form of economic reward. The concept of morality merges at this point with the decrease and increase of social capital. Hardin rightly describes that if we ask the citizen to desist in exploiting the commons, we communicate to him two contradictory meanings. The intended communication is that we openly condemn you if you don’t act as a responsible citizen. The unintended communication is that you are a naïve simpleton if you don’t exploit the commons while everybody else does. Only when asking for responsibility does not remain asking for something in exchange for nothing, will commons preservation become a scalable reality.

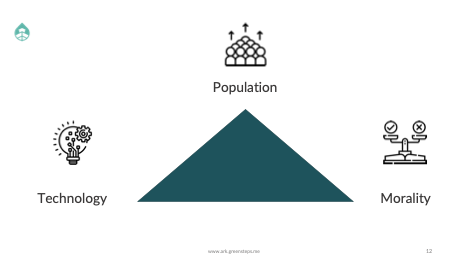

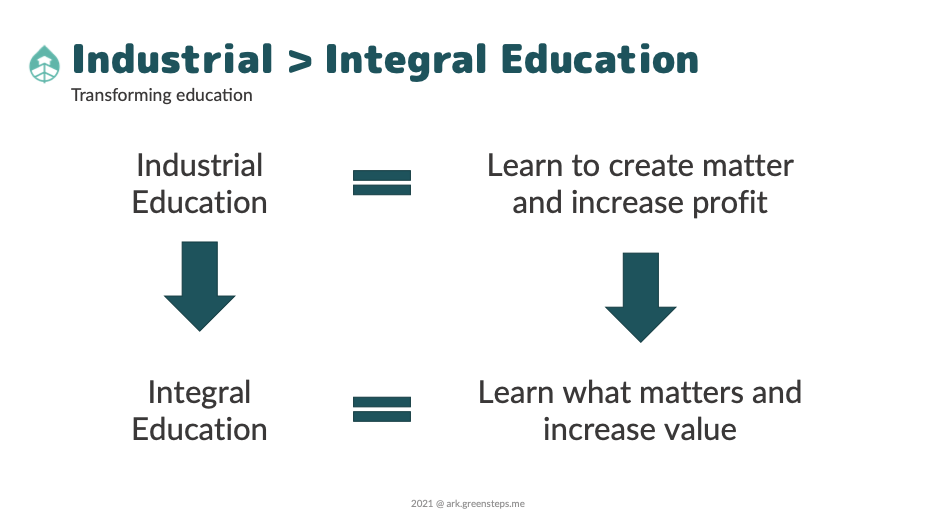

What emerges before our eyes is a triangle of morality, technology and population. Hardin tells us that morality is system-sensitive and argues that the increase of population changes moral standards to such an extent that some people are being morally entitled to deny others procreation. While I subscribe to Hardin’s demand that there should be a minimum education standard for parenting a child, I believe that we do not agree on the curriculum of such education. Is it one which rests on empathy and compassion or one which strengthens greed and competition?

We moreover need to ask ourselves if morally questionable behavior like e.g. the wasteful exploitation of fishing grounds was any less wrong in the preindustrial past than it is today. Morality is in my opinion less system-sensitive than one might think, but the execution of moral behavior yields substantially different impact when scaled to eight billion actors. If our societies today still had a moral codex as described by Snyder (6) similar to indigenous ethnicities of the past which respect the commons and in which the elders teach the young that any wasteful exploitation renders survival in the ecosystem impossible, we would not need a change.

No Technical Solution Problems

Yet, here we are in the 21st century and the planet as a global commons and the smaller local commons it entails face destruction. What we need is certainly a culture which emphasizes our role as stewards of the planet, one which strengthens the moral management of commons. Hardin describes overpopulation as a “no technical solution problem”, but commits a logical error as he proposes contraception as a technological solution to overpopulation. He builds the category of “no technical solution problems” by referring to nuclear proliferation, another major issue of the cold war era during the 1960 and 1970s which confronted governments with the dilemma of steadily increasing military power and steadily decreasing national security.

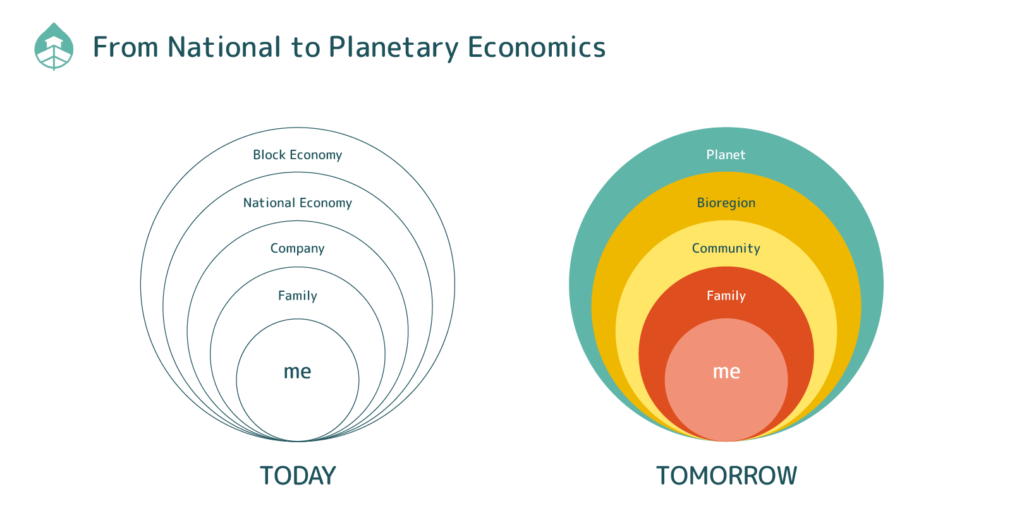

By building his case for population control on the national interest of security Hardin points at the moral dimension of national economics: as long as nation states compete for resources on a finite planet, there is dreadful waste with the arms race between powerful nations only being the tip of an iceberg. In a world which has changed its moral operation paradigm from having to being, we would not create artificial scarcity but reasonable abundance. Take energy as an example: if humanity could agree on a global energy production and distribution plan, system redundancies and inefficiencies would disappear and social stability in hitherto fragile regions could emerge.

The category of “no technical solution problems” exists only between nation states which have failed to switch from competition to cooperation. Once cooperation has turned into the operation default mode, synergies appear hand in hand with new technical solutions – on every level of human activity, both local and global. What has happened is not a change of morality but a change of system. Cooperation, sharing and compassion would have been possible at any time in human history, but it is only now as we reach the limits of the Earth’s carrying capacity that we might be compelled to give these values a shot – in absence of alternatives.

The tragedy of the commons is indeed a tragedy of human consciousness. Each man is locked into a system that compels him to fight for survival and increase pleasure to be able to endure this monotone struggle – in a world that is potentially abundant with joy. Ruin is the destination toward which all men rush, each taught to pursue individual interests in a society that has abandoned the believe in collective growth and responsibility for each other (7).

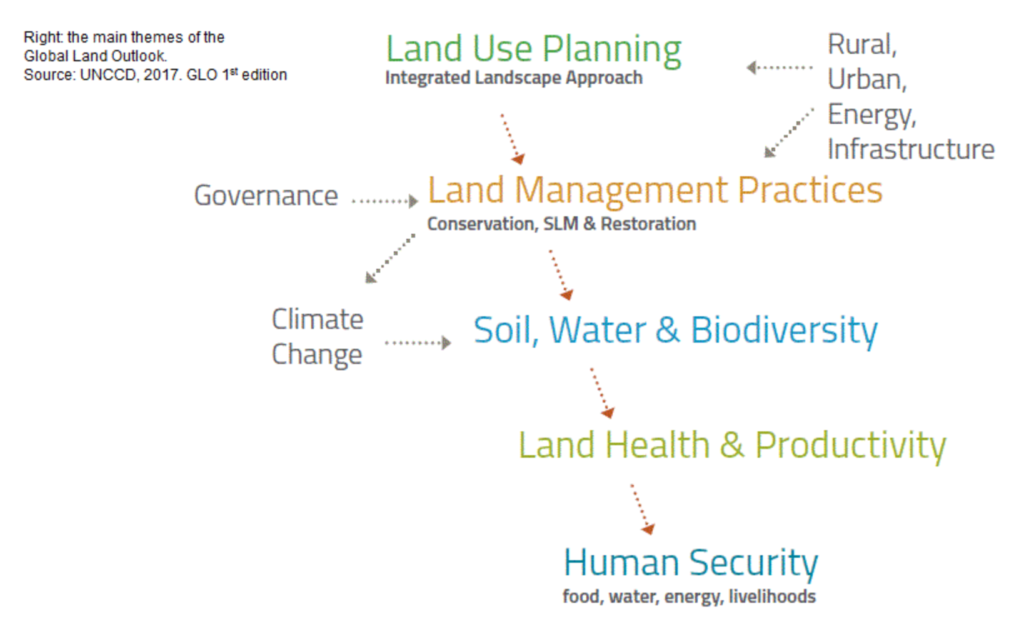

Environmentalism must eventually address the question of land use and thereby turns into a social rather than an ecological issue. Depending on the perspective we take, we might come to the conclusion that social arrangements are ecological arrangements, since the human being is not different from, but an integral part of nature. Hardin applies all his intellectual skills to circumnavigate this unavoidable subject and argues for a continuity of the private property system. In communist countries like China, all land is owned by the central government. Alienation from and destruction of planet and people has not improved in this system as far as we can tell by know. Therefore, we must explore other forms of land use as proposed e.g. by Georgism (8).

The Educational Value of Commons

Hardin makes in his essay a decisive case to either reduce the human population or shut down the commons one after another. He presents National Parks as another instance of the working out of the tragedy of the commons and discusses several options to preserve them:

- sell them off as private property

- keep them as public property and allocate the right to enter them

- on the basis of wealth

- on the basis of merit

- by lottery

- first-come, first-serve principle administered by long queues

While some of these restrictions are already practiced in different parts of the world, e.g. the limited right to enter based on lottery (Japan) or wealth (China), we can take the case of National Parks as a starting point to discuss the educational value of commons and if a society can operate in full sanity if they are either in private property or their access is regulated through capitalist practices.

There is increasing evidence that appreciation of nature cannot be learned in classrooms but must be experienced in the outdoors. The experience of ecosystems is essential to their understanding. Yet, private property has destroyed the commons as they have been experienced by our ancestors, and in particular city dwellers, who make up between 70 and 90% of any given industrialized country, are deprived of the possibility to learn first-hand how their actions impact the ecosystem they live in.

The commons have been defined as “the undivided land belonging to the members of a local community as a whole.” This definition fails to make the point that the commons is both specific land and the traditional community institution that determines the carrying capacity of its various subunits and defines the rights and obligations of those who use it, with penalties for lapses. Because it is traditional and local, it is not identical with today’s “public domain,” which is land held and managed by a central government. (8)

The tragedy of the commons is therefore not their uncontrolled depletion but the lack of truly democratic institutions which determine use and abuse for the benefit of the community at large. The tragedy of commons is in all essence a tragedy of community. If humanity was like a large community which perceives all natural resources as a commons (as proposed by Georgism), then access to resources like housing and food or a basic income could be distributed on the condition of agreed upon behavior.

Morality is not as system-sensitive as Hardin assumes – only the impact of amoral behavior is. The Buddhist who decided two millennia ago to abstain from devouring meat has made in consequence the same moral choice which most modern vegetarians make – indifferent of global population size. Some individuals require external conditions to transform, others reach that point through internal thought. Peak world population is an opportunity for transformation of humanity on a large scale. This transformation must entail the enlargement and opening up of commons paired with the establishment of decentralized institutions which govern the conditions upon which they may be used. Distributed value accounting, which tracks the contribution to a commons could would be a moral technology which could solve the human problem of power abuse and profit seeking (10) by minimizing power concentration through a decentralized autonomous organization (11).

We can therefore conclude that all problems can find a technical and systems appropriate solution as soon as the moral solution has been agreed upon. If we envision a world of reasonable abundance, we will find that distributed value accounting and post-industrial forms of e-governance can bring about sustainable development. It however requires that those who are stuck in a mode of having switch to sharing. They are well advised to switch soon, because education is a process which lasts a generation or more if deeply ingrained patterns of greed and apathy shall change.

Further reading:

- Garrett Hardin: The Tragedy of the Commons

- Knut Wimberger: Overpopulation, Technology and the Decline of Democracy

- History of the Oral Contraceptive Pill

- China’s One Child Policy

- Gus Speth on Shared Planet: Religion and Nature, BBC Radio 4 (1 October 2013)

- Gary Snyder, The Practice of the Wild

- Steven Cutts, Happiness

- Georgism

- Gary Snyder, The Practice of the Wild

- Aldous Huxley, The Politics of Ecology

- Steffen Ummelmann, DAO as the organizational structure of the future

- Global Land Outlook Report 2017

- Steven Cutts, The Turning Point

“On The Value and The Management of Commons” için bir yanıt

[…] the planet as a single ecosystem which we need to protect jointly, if we do not want to perish. The tragedy of the commons has transformed in dimension: instead of a local sheep pasture the commons which needs to be […]